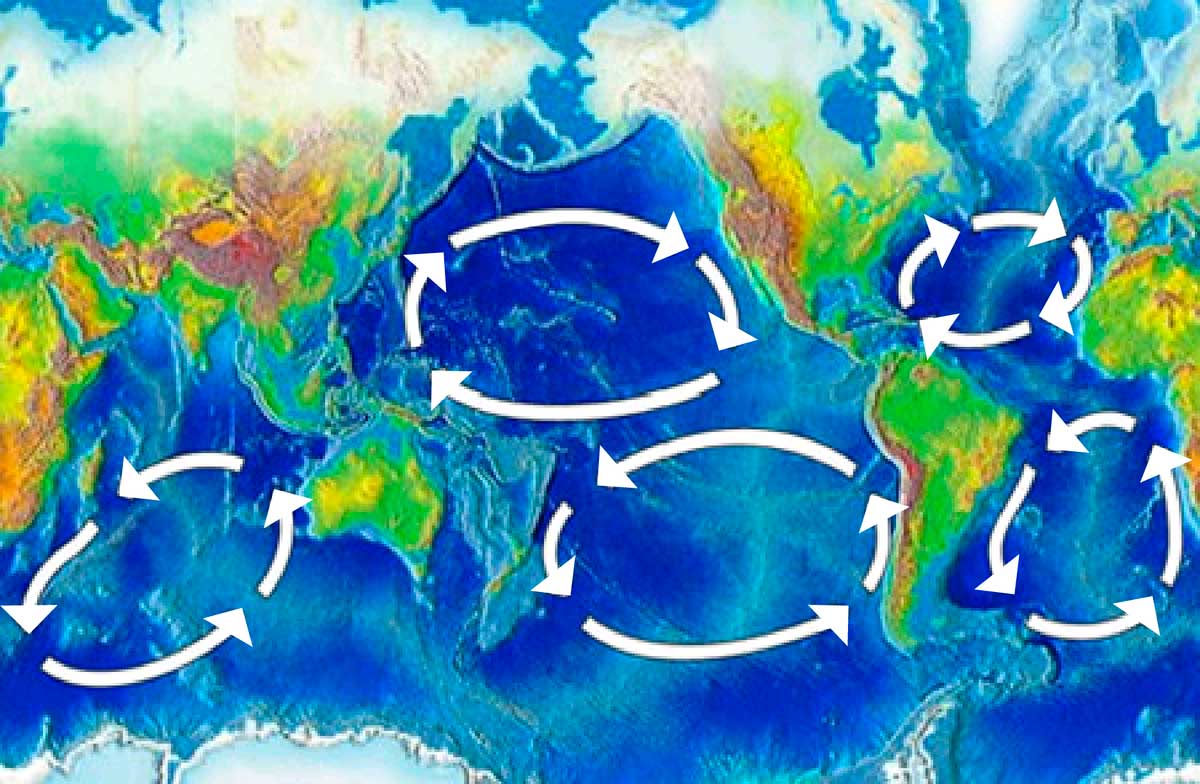

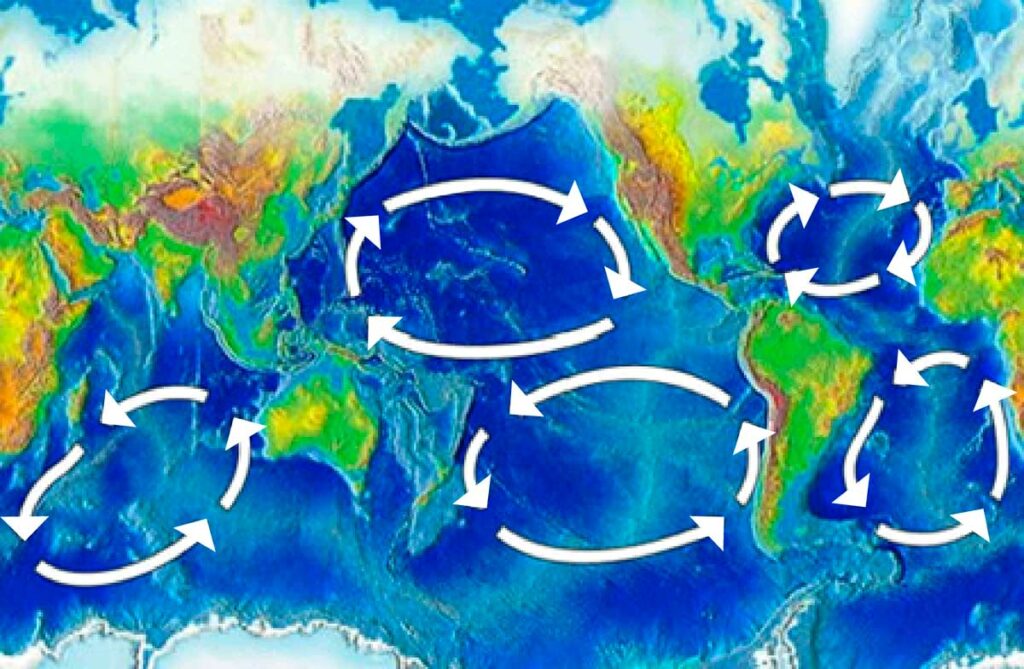

What Is an Ocean Gyre?

In the oceans, marine currents form gyres—vast whirlpools located at mid-latitudes. These circular movements are driven by trade winds, variations in water density, and the Coriolis effect (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016).

Plastic Waste Trapped in the Gyres

Plastics released by human activity are carried by ocean currents and eventually accumulate in five major gyres: two in the Atlantic, two in the Pacific, and one in the Indian Ocean. In the North Pacific Gyre, researchers have identified debris bearing nine different languages, with some items dating back to 1977 (Nature, 2018).

The Myth of the “Plastic Continent”

Sailor Charles Moore revealed this phenomenon in 1997 and popularized the term “plastic continent” (Océan plastique, Nelly Pons, 2020). However, these zones do not form visible islands of waste. They are primarily composed of microplastics, dispersed throughout the water column down to 30 meters deep, forming a true “plastic soup.”

Microplastics: Fragmentation and Invisible Danger

Plastics break down into microplastics through photodegradation, mechanical abrasion, and biodegradation (Nature, 2018). Once in this form, they become nearly impossible to remove from the marine environment.

Despite thousands of nautical miles sailed by Ekkopol’s crew, none have observed these “continents”: the waste is invisible on the surface, suspended between layers. Its slow degradation poses a direct threat to biodiversity.

Ecological Impacts of Microplastics

The effects of microplastics are severe and likely underestimated. Their ingestion by marine organisms leads to the spread of pollutants in biological tissues. For example:

- Whales are contaminated by phthalates (WWF Report, 2018).

- The bacterium Prochlorococcus, essential to oceanic photosynthesis, experiences inhibited growth (Scientific Reports, 2019).

- Polar bears suffer reproductive disorders (Greenpeace Report, 2018).

🎥 Watch the explanatory video on YouTube

Gyres Are Not the Only Marine Dumping Grounds

Gyres concentrate plastics, but the waste continues its journey elsewhere (Vincent Perazio, 2016

). Imagining we can simply collect it from the heart of the oceans is an illusion. These materials become “ultimate waste,” impossible to eliminate (Article L541-2-1).

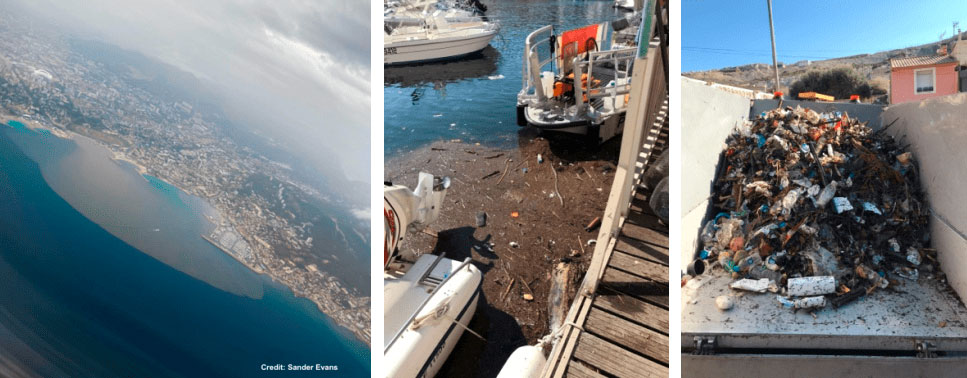

Global Plastic Pollution: Beyond the Gyres

High concentrations of microplastics are also found:

- Off industrial and urban zones.

- In the Mediterranean, which holds 7% of the world’s microplastics (WWF Report, 2018).

- In the Java Sea and the Strait of Malacca, where Emilien Pierron observed exceptional pollution.

- In Antarctica, near the Weddell Sea, where Greenpeace detected microplastics in 7 out of 8 water samples and persistent chemicals in 7 out of 9 snow samples (Greenpeace Report, 2018).

Conclusion: Prevention Over Cure

Gyres have helped raise public awareness, but they are merely a symptom of global plastic pollution. The oceans cannot be effectively cleaned. It is therefore essential to reduce plastic waste at the source and prevent its dispersion.

[i] Océan plastique, Nelly Pons, 2020, p. 65

[ii] The Ocean Plastic Crisis, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016, p. 15

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Accumulation of microplastics in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, Nature, 2018, p. 508

[v] Une partie d’entre eux sont classés comme « substances toxiques pour la reproduction »

[vi] Plastic leachates impair growth and oxygen production in Prochlorococcus, the ocean’s most abundant photosynthetic bacteria, Sasha G. Tetu, Indrani Sarker, Verena Schrameyer, Russell Pickford, Liam D. H. Elbourne, Lisa R. Moore, Ian T. Paulsen, 2019, p. 371-379

[vii] Océans, le mystère plastique, Vincent Perazio, 2016

[viii] Pollution plastique en Méditerranée, sortons du piège !, rapport du WWF, 2018

[ix] Microplastics and persistent fluorinated chemicals in the Antarctic, rapport de Greenpeace, 2018

[x] article L541-2-1 sur les déchets ultimes